Generation 100 - CERG

Generation 100: Does exercise make older adults live longer?

The Generation 100 exercise study followed more than 1500 women and men in their 70s for five years. The aim was to find out if exercise gives older adults a longer and healthier life, and we also compare the effect of moderate and high-intensity exercise. The study is the largest of its kind, and the five-year testing of the participants was completed in 2018.

The main results were published in The BMJ on October 8, 2020, and are summarized in the animated video at the top of this page. A more thorough summary of the main results follows below.

Background for the study

Demographic data indicate a tripling of the population aged 60 years and older by the year 2050. Thus, research on how to achieve healthy aging is needed and required.

Generation 100 is the largest randomized clinical study that evaluates the effect of regular exercise training on morbidity and mortality in older adults. Inclusion of the participants in Generation 100 started in 2012.

Since then, a total of 1567 participants have been randomized to either five years of supervised exercise training, or to a control group. The exercise group was further randomized to either two weekly sessions of high intensity training or to moderate intensity training. The participant could perform most of the exercise sessions by them self if they wanted to, but all had to attend at least one supervised session every sixth week. The control group was instructed to follow national physical activity guidelines.

Thorough clinical examinations and fitness tests, as well as questionnaires, were administered to all participants at baseline, at one year (2013/2014), three year (2015/2016), and five year follow up (2017/2018).

The results from the Generation 100 Study contribute to improved understanding on how older adults can stay at good health for as long as possible. Exercise as medicine is a relatively cheap, accessible and available treatment that can benefit a large proportion of the population.

High-intensity interval training improves health in older adults

High-intensity interval training for five years increases quality of life and improves cardiorespiratory fitness more than moderate exercise. However, we can still not be certain that it's more effective to improve longevity in the elderly.

High survival

Among 70-77-year-olds in Norway in general, 90% survive the next five years. In the Generation 100 study population, an impressive 95.4% of the participants survived.

The high survival is likely to some extent caused by the exercise performed by the participants in all the three groups in the study. Our data shows that even the control group maintained a high level of physical activity throughout the period. Although this group was not offered organized exercise, the participants may have been motivated by the regular fitness and health check-ups throughout the study.

However, our findings can not make us completely sure that exercise prolongs life for older adults. The high survival in all groups is probably partly explained by a "healthy participant bias". Those who signed up to participate in the Generation 100 study had relatively good health, were relatively physically active and probably had high motivation for exercise in the first place.

Trend towards lower risk of early death with high intensity

In the high-intensity interval training group, 3% died during the study period. In the moderate intensity exercise group, 5.9% of the participants died. The difference between the groups is not statistically significant. However, the trend is so clear that we would encourage health authorities worldwide to recommend high-intensity exercise for older adults – at least as supplement to other types of exercise.

In the control group, 4.7% of the participants died during the five-year period. We found no difference when we compared the survival in the two exercise groups combined and the survival in the control group. Furthermore, the risk of dying from cardiovascular diseases or cancer did not differ between the three groups.

Active control group

The participants in the control group exercised more than we thought they would, which makes it challenging to interpret our results. Actually, 20% of the participants in this group exercised regularly with high intensity. Thus, they performed more high-intensity training than the moderate group but less than the high-intensity group. This may explain why they ended up in the middle also in terms of mortality.

Another possible reason why the study does not give us completely clear answers, could be that not all participants in the two exercise groups exercised according to the study protocol. Only half of the participants in the high-intensity group actually performed regular high-intensity interval training, whereas more than 10% of the participants in the moderate group exercised frequently with high intensity.

More health effects with high-intensity training

Both physical and mental quality of life were better in the high-intensity group after five years than in the other two groups.

High-intensity interval training also had a greater effect on cardiorespiratory fitness after one, three and five years, compared to the other two groups. Higher fitness is closely linked to a lower risk of premature death, so this improvement may possibly be a reason why the high-intensity group apparently had the highest survival.

The participants in the other two groups in the Generation 100 study also managed to maintain their cardiorespiratory fitness throughout the five-year period. This is quite unique for people in this age group, with an expected drop in fitness of 20% over a ten-year period. This indicates that the participants in all three groups of the Generation 100 Study have been more physically active than what is usual for men and women in their 70s.

Other results from the Generation 100 project

Follow the links below to read easy-to-understand summaries of all the published results from the Generation 100 Study. Those particularly interested can read the research articles in the scientific journals where they are published.

- Following general exercise recommendations may be better for brain cells

- Better fitness links to reduced presicription of drugs for mental health problems

- How does exercise intensity affect signal conduction in the brain of the elderly?

- Can high fitness protect the elderly from structural brain impairments?

- Does exercise affect the progression of white spots in the brain?

- Can exercise reduce the risk of mild cognitive impairment?

- Does fitness impact cognitive function?

- Does interval training lower cardiovascular risk more?

- 4x4 interval training is beneficial for "the good cholesterol"

- Can exercise prevent loss of brain volume?

- 70-year-olds with good fitness have higher blood volume

- Who are most physically active: Norwegian or Brazilian older adults?

- New fitness genes link to cardiovascular health

- What kind of exercise is most likely to increase fitness?

- What kind of exercise does older adults prefer?

- Which older adults are more likely to drop out of an exercise program?

- Does weather influence physical activity in the elderly?

- How fit is the average 70-year-old?

- Obesity and low fitness linked to higher cardiovascular risk

- More metabolic syndrome among inactive older adults

- Is lung function important for fitness in older adults?

- The faster walk, the more steps during a day

- Are older adults active enough?

- Is a lot of sitting OK for the fittest?

- How does fatigue impact activity level?

- What time of year is the activity level highest?

- New threshold for pshyical activity intensity in the elderly

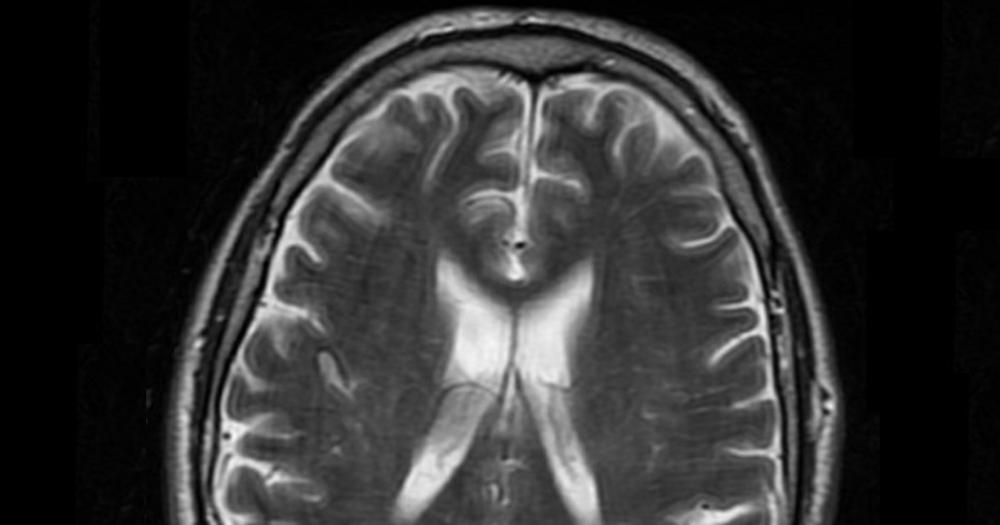

Avoiding very high-intensity exercise and following the health authorities' physical activity recommendations may be the most beneficial for the elderly in terms of keeping healthy brain cells in the hippocampus. After three years of exercise, it was the control group of the Generation 100 study that had the highest N-acetylaspartate:creatine ratio in the hippocampal body, whereas the choline:creatine ratio was lowest in the participants who reported to exercise most intensively.

The neurochemical N-acetylaspartate signals healthy neurons, while choline is important for the cell membranes of the nerve cells. The hippocampus is a part of the brain that, among other things, is important for our memory. However, the differences we found does not seem to have affected the cognitive function of the participants. On the contrary, it was actually the participants with the lowest choline:creatine levels in the hippocampal body who scored highest on the cognitive test.

In the anterior part of the hippocampus, we found no difference in the levels of neurochemicals, neither between the groups nor based on reported exercise intensity. We also investigated whether maximum oxygen uptake had an effect on the metabolites, but neither fitness level at the same time nor changes in fitness over time played any role.

In the Generation 100 study, men and women aged 70 to 77 were randomly allocated to organized exercise follow-up for five years, or to participate in the control group which were told to follow the authorities' recommendations for physical activity. This substudy includes analyzes from 63 of the participants, and we measured the levels of N-acetylaspartate, choline and creatine by performing MR spectroscopy after three years. Most of the participants exercised well throughout the period, and the participants in the control group to a high degree followed the recommendations to exercise with moderate intensity 30 minutes most days of the week.

Older adults with poor cardiorespiratory fitness seem to be able to reduce the use of medication for anxiety, depression and sleep problems by improving their fitness. For those who already have a high maximum oxygen uptake, it seems less appropriate to further increase fitness.

The results are based on data on drug use and fitness among over 1,500 participants in the Generation 100 study. We measured the fitness of all the 70–77-year-old participants four times over five years, and obtained information on the use of medicines from the Norwegian Prescription Database throughout the entire period.

We found the highest use of medication for mental disorders among the least fit participants. Thereafter, the use of such drugs was gradually reduced with better fitness, up to a fitness number of 40 ml/kg/min. For the small number of participants who had even better cardiorespiratory fitness than this, drug use increased somewhat again.

The results were similar when we analyzed the use of antidepressants separately. On the other hand, we found no definite connection between cardiorespiratory fitness and the use of sleeping pills or anti-anxiety drugs, respectively.

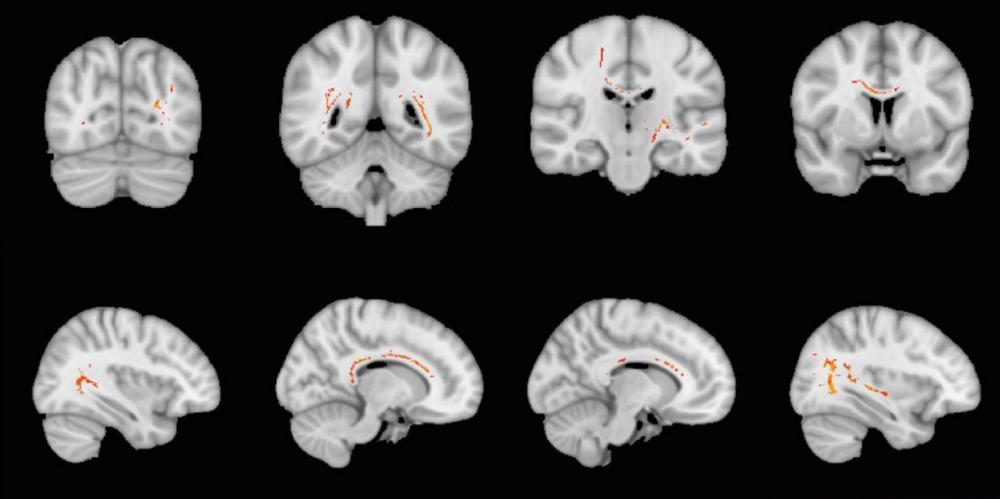

The wiring network in the brain was not better preserved in the Generation 100 groups that were offered organized exercise, compared with the participants who were advised to exercise on their own. Nevertheless, the results suggest that high fitness and high-intensity training are beneficial for maintaining better structure in this network.

Good signaling in the brain depends on intact nerve fibers and a thick layer of myelin that insulates these fibers. Together, nerve fibers and myelin form the white matter of the brain. In this study, we used MRI to examine the structural organization of white matter in 105 of the 70-77 year old participants in the Generation 100 project. The measurements were made at start-up and after one, three and five years of exercise follow-up, respectively.

Myelin ensures that molecules move along the nerve fibers instead of diffusing away from the fibers. A high degree of myelination therefore indicates good conduction capacity of nerve signals in the brain. Our results show that elderly people with high exercise capacity - in all three groups - had both a greater degree of myelinated nerve fibers and of molecules that moved along the nerve fibers. However, this correlation was strongest at start-up and after one year, and decreased after that.

The study also found a link between higher self-reported exercise intensity and better structure of the white matter of the brain. Here, too, the association was only present at the beginning of the study period. The results may be an indication that high-intensity training and high fitness protect against damage to the wiring in the brain in the elderly. At the same time, it may seem that this effect diminishes as one approaches 80 years.

In general, the findings agree well with other results on exercise and brain health from the Generation 100 project (see here, here, here, here and here).

The Generation 100 study showed no effect of organized exercise follow-up on avoiding age-related changes in the structure of different parts of the brain. On the other hand, the participants who started the study with high aerobic capacity had better preserved structural complexity of cerebral gray matter - and specifically in the temporal lobe - compared with those who were less fit.

Better maintenance of fitness throughout the five years of the study was also associated with better preserved structure in the temporal lobe. This area of the brain is sensitive to physiological aging and the development of Alzheimer's disease.

In Generation 100, three groups of older women and men exercised differently, with two of the groups being offered organized exercise twice weekly. This substudy includes the 105 participants who underwent MRI scans of the brain before and during the study. A new method was used to assess structural complexity more accurately in different parts of the brain.

After five years, the measurements of structural complexity showed equal reductions in all three exercise groups. But a high maximum oxygen uptake was linked to better preserved complexity in parts of the cerebrum. The level of fitness had, however, no effect on the thickness of the cerebral cortex.

The results are largely reminiscent of other recently published findings on exercise and brain health based on the Generation 100 study. The general conclusion seems to be that high age-related fitness can be a key to maintaining important brain functions and avoiding wasting of brain tissue for the elderly.

We found no beneficial effect of high fitness or long-term organized exercise on the development of white spots in the brain of older adults. These spots can be seen on MRI, and are common after the age of 50. The spots are scars in the wiring in the brain, and are associated with impaired gait function, cognitive impairment, depression and stroke. Neither in the participants who were offered organized interval training with high intensity, nor in those who could attend moderate training sessions, did the growth of these scars develop differently than in those who exercised on their own.

The study includes 105 of the participants in the Generation 100 study. Their brains were checked with MRI before, during and after the five-year exercise period. The extent of white spots increased in all three groups, especially during the last couple of years of the 5-year period. The other three studies we have published on brain health in the Generation 100 study show that high fitness protects against cognitive impairments. However, we found no association between fitness and the development of white spots. Nor did those who improved their fitness during the study have slower development of white spots in the brain than the rest of the participants.

The exercise follow-up in the Generation 100 study may have given older men, but not older women, better cognitive function and a lower probability of mild cognitive impairment. Both men and women who maintained or increased their fitness during the study had better brain health than those with lower fitness levels, regardless of whether they were part of the groups that had received organized training follow-up or not. The greater the increase in fitness, the lower the likelihood of having mild cognitive impairment.

The study includes 945 of the 70-77 year old women and men who participated in the Generation 100 study. They had been randomly assigned to five years of exercise follow-up with intensive or moderate intensity, respectively, or to self-training. After the training period, they completed the MoCA test, which, among other things, tests short-term memory, executive function and ability to orientate in time and space. The men who had been part of the training groups scored higher on the test than the men in the control group, and they also had a 32% lower probability of mild cognitive impairment. Participants whose cardiorespiratory fitness decreased during the study had a 35% higher probability of mild cognitive impairment than those who maintained or improved their fitness over the five years.

The organized exercise follow-up in the Generation 100 study did not make the participants better at solving cognitive tasks. Neither the group that was offered moderate intensity exercise sessions nor those who attended intensive interval training regularly for five years performed better than the control group. For example, all groups' abilities to remember the location of an object and memorizing words were similar. Moreover, the exercise follow-up had no effect on planning, the ability to separate similar memories or process information quickly. It is worth noting that the 70-77 year old participants on average had the same cognitive abilities after five years as at the start of the study, and they even improved on some of the tests.

In addition, we saw that the participants with high cardiorespiratory fitness at the start of the study, had better cognitive abilities throughout the study than those with lower fitness. We also saw an improvement in the so-called working memory, which concerns remembering and processing information while performing cognitive tasks, among the participants who improved their fitness during the study period. The study includes 106 of the Generation 100 participants, and they conducted cognitive tests on a web-based portal both at start-up and after one, three and five years.

Five years of organized exercise follow-up for older women and men in the Generation 100 study, did not reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease significantly, compared to exercising on your own. After three years, however, a score for overall cardiovascular risk was significantly lower in the group that performed intervals with high intensity, and we saw a tendency for the same also after five years. Organized interval training for five years also resulted in better cardiorespiratory fitness, lower resting heart rate and lower BMI.

The main results from Generation 100 showed higher survival than expected among the 70-77 year old women and men who participated, and especially in the group that was randomized to interval training. The 1567 participants in the study were randomly divided into three groups, who were either offered to attend interval training or moderate training two days each week, or received general advice on moderate physical activity. The new research article examines whether traditional risk factors such as waist circumference, blood pressure, cholesterol profile and blood sugar changed differently in the three groups, and interval training tends to be most effective in improving the overall levels of these risk factors. Those who were offered moderate exercise sessions had no greater effect than those who were advised to be active on their own. A good number of participants in all groups trained differently than they were asked during the period, which makes it challenging to interpret the results. At the start of the Generation 100 study, the levels of risk factors were also healthier than we usually see in the elderly, which may also be an explanation for why we did not find major changes or differences between the groups.

High-intensity interval training could increase HDL cholesterol in older men

The men in the Generation 100 Study who performed 4x4 intervals with high intensity twice weekly increased their levels of HDL cholesterol by more than 6 % during the first three years of the study. After five years, the levels were still almost as high as when the study started. In comparison, HDL levels decreased by 6-7 % in the men who exercised at moderate intensity or were adviced to follow the general exercise recommendations. The HDL particles removes cholesterol from the blood vessel walls, and higher levels could reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases.

In women, HDL cholesterol levels decreased by 2.6% after five years of interval training, compared to around 7% in the other two groups. However, the difference between the groups was not statistically significant. On the other hand, the men and women who improved their cardiorespiratory fitness the most, also had the most beneficial change in HDL cholesterol levels during the study. The Generation study recruited 1567 older adults aged between 70 and 77, and this particular analysis includes the approximately 50% who actually exercised according to the study protocol.

Organized exercise follow-up did not prevent loss of brain cells compared to giving general exercise advice without offering organized exercise sessions. However, Generation 100 participants with high cardiorespiratory fitness at the onset of the study had thicker cerebral cortex throughout the five-year exercise period than those who were less fit.

To check for changes in brain volume and the thickness of the cerebral cortex, we performed MRI scans of the brains of 105 of the 70-77 year old participants in the Generation 100 study both before, during and after the exercise intervention. The group that exercised on their own without organized follow-up had less than age-expected atrophy of the hippocampus and the foremost part of the brainstem. In the groups exercising at high and moderate-intensity, respectively, the atrophy was somewhat greater than among those who exercised on their own, but still not higher than what is expected for people in their 70s.

High cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with high blood volume, high hemoglobin mass and a high volume of red blood cells in the elderly. The link between blood volume and fitness can be partly explained by the fact that older people with good fitness are more physically active than less fit elderly people. The amount of physical activity did however not affect the relationship between fitness, red blood cells and hemoglobin mass. This agrees well with what we already know that physical activity can increase blood volume, whereas genetic predisposition probably has the greatest significance for hemoglobin mass and red blood cell volume.

It is well known that high blood volume is crucial for high maximum oxygen uptake and good endurance performance among athletes, but this study is among the first to show that this relationship also applies to healthy elderly people. 50 participants from the Generation 100 project participated, half of whom were in good shape for their age, while the rest had a low maximum oxygen uptake. We measured their blood volume using so-called CO re-breathing, where you inhale a certain amount of carbon monoxide mixed with pure oxygen for two minutes. We also took blood samples from the participants and equipped them with an activity monitor for seven days to find out how physically active they were.

Older adults in Norway are slimmer than older adults in Brazil, and also have better grip strength and less triglycerides in the blood. Most seniors in both countries report being physically active at least two days each week. Norwegian older adults in general have higher cholesterol levels and blood pressure than Brazilians, but the proportion who use blood pressure medication is more than twice as high among Brazil's elderly. According to the study, an equally high proportion in both countries have the metabolic syndrome, which is an accumulation of risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The differences in BMI and waist circumference seem to be explained by the fact that older people in Norway have a higher level of education than older people in Brazil. There was no difference when we repeated the analyzes without including the Brazilians who had no secondary education. 310 participants from our Generation 100 study and 255 seniors from Ribeirao Preto in Brazil are included in the study. 80% are women.

We have found six new genetic variants that link closely to having high or low cardiorespiratory fitness. Having a higher number of the favourable genetic variants – and a lower number of the bad ones – is linked to lower waist circumference, fat percentage, BMI and blood lipid levels. Furthermore, to have good fitness genes is associated with a lower likelihood of using blood pressure medication. We know that genes are quite important for maximum oxygen uptake, and this is the first major study to look for genetic variants associated with directly measured cardiorespiratory fitness.

In the study, we analyzed more than 120,000 unique genetic variants in 3470 healthy women and men who measured their maximum oxygen uptake during the HUNT3 Fitness study. We found that 41 of the genetic variants were closely related to the fitness of these participants, even after adjusting for gender, age and self-reported activity level. Six of the same genetic variants were also significantly associated with high fitness in the validation cohort of 718 elderly who participated in the Generation 100 study. Further experiments indicated that the genetic variants in question affect gene expression in adipose tissue, skeletal muscle and heart.

High-volume high-intensity interval training is more likely to improve cardiorespiratory fitness than continuous exercise at moderate intensity. One third of those who performed regular interval training with at least 15 minutes of high intensity per session increased their fitness, even when we used strict criteria to define a likely response. In comparison, one fifth of those who exercised at moderate intensity for at least 30 minutes per session were responders.

The article includes data from 18 trials and 677 participants from five countries. We have included studies with healthy adults of all ages, as well as higher risk populations and patients with coronary heart disease. A gain of at least 5 ml/kg/min was defined as response to exercise. The studies with the longest duration and highest exercise loads had the most significant number of responders, indicating that at least some of those who were deemed non-responders would respond with an increase in training duration, frequency or intensity.

More than half of the self-reported activity among participants in the moderate intensity exercise group of the Generation 100 Study was performed as walking. Walking was also the most popular activity among the participants in the high intensity exercise group, but these participants did more cycling and jogging compared to the moderate group. Moreover, the findings show that older adults are able to perform high intensity exercise without strict supervision.

Both groups preferred to exercise outdoors, and only one third of the sessions were performed indoors. We also found that women more often than men exercised together with others. The information is gathered from exercise diaries from the first year of the Generation 100 Study, and includes almost 70 000 exercise logs in total.

Less than 15 % of the 1500 participants dropped out of the Generation 100 study during the first three years. Low education, low grip strenght, low cardiorespiratory fitness and low levels of physical activity were significant predictors of dropping out. Participants with reduced memory status were also more likely to drop out. The results give important information about potential factors that increase the risk for dropping out of long-term exercise programs in older adults..

The Generation 100 study aims to find out if exercise can give older adults longer and healthier lives. The participants are randomized to three group, of which two are exercise groups. Our results also show that participants randomized to exercise – and thus more regular follow-up appointments – aslo were more likely to drop out than those randomized to the control group.

Unfit older adults are less physically active during rain or snow, whereas fit older adults don't seem to let precipitation influence activity levels. Moreover, older adults are more physically active with increasing temperatures. The findings suggest that bad weather might be a barrier towards physical activity in unfit older adults.

To find these results, we studied accelerometer data from 1291 participants in the Generation 100 study. Hour-to-hour data on temperature and precipitation were collected from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute.

At baseline testing in the Generation 100 Study, we measured the maximum oxygen uptake of 1537 men and women from Trondheim born between 1936 and 1942. The results are by far the largest data material in the world that says something about expected physical capacity among older women and men.

The men achieved an average maximum oxygen uptake of 31.3 ml/kg/min. The women had lower values: 26.2 ml/kg/min. Women and men who had cardiovascular disease had 14% and 19% lower physical capacity, respectively, than those who were healthy. The ability to lower the heart rate quickly after maximum exertion was also reduced among heart patients.

It can be useful to include both physical fitness and body composition when assessing the risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly and motivating them to lead a health-promoting lifestyle. The Generation 100 study shows that participants who have both low maximum oxygen uptake and unfavorable body composition probably have an extra high risk of cardiovascular disease.

The probability of having an accumulation of several risk factors was six times higher among older adults who had poor fitness and a body mass index (BMI) indicative of overweight or obesity, compared with slimmer participants with higher fitness. Men and women with poor cardiorespiratory and high fat percentage or high waist circumference also had a fivefold increased likelihood of high cardiovascular risk.

We have previously developed a new method for measuring physical activity in the elderly. Our results now confirm that using this method can tell us something about health. Data from the activity measurements of more than 1000 Generation 100 participants showed a higher incidence of metabolic syndrome among those who did not satisfy the minimum recommendations for physical activity based on relative intensity. Metabolic syndrome means that you have at least three of the common risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

The commonly used absolute intensity model, on the other hand, was not associated with metabolic syndrome. The results may therefore indicate that our new threshold values for moderate and intensive physical activity measured with an accelerometer provide a more accurate description of the amount of activity sufficient to provide good health in the elderly.

Our Fitness Calculator is even more accurate for older adults if you add measurements of lung function. In the Generation 100 Study, we tested how much air the participants managed to exhale during the first second after filling their lungs to the maximum. We also measured the capacity to transport oxygen from the alveoli to the blood, and also the levels of hemoglobin, which transports oxygen in the blood.

When we included these three values in the Fitness Calculator, we were able to calculate the actual fitness of the participants even more accurately, especially for men. This suggests that the lungs may be a limiting factor for physical capacity in older men in particular.

Older adults who walk fast achieve more steps in a day than older adults who walk slowly. In addition, walking slowly was the only gait pattern factor that could predict the Generation 100 participants most likely to reduce their activity level during the first year of the study.

Step frequency and step length also had an effect on the activity level: the shorter the length and the higher the frequency, the less physical activity.

Using gait patterns from 86 healthy Generation 100 participants, we have also compared two computer programs that analyze gait.

At the start of the Generation 100 study, only 29% of the participants were as physically active as the health authorities recommend – if the activity level is measured with the standard method for accelerometers. If, on the other hand, we use our method, which takes into account that older people usually have lower physical capacity than younger people, as many as 71% were physically active enough.

The study also shows that there were more women than men who reached the recommendations based on our new method, which uses age-relative rather than absolute training loads. The most common activity in both women and men was walking.

70-77-year-olds with high cardiorespiratory fitness even though they sit a lot during the day, do not have higher risk of cardiovascular disease than equally fit older adults who sit less. The results indicate that having a high maximal oxygen uptake can offset the negative cardiovascular consequences of sitting still among the elderly. The study also shows that low fitness is closely linked to increased accumulation of risk factors no matter how little or how much an older person sits still during the day.

Data from the accelerometers showed that the Generation 100 participants on avarage were at rest 75% of their awake time. Just over a third of women and men complied with the health authorities' minimum recommendations for physical activity. But even among those who do not meet these recommendations, high fitness seems to protect against the accumulation of risk factors. On the other hand, those with low fitness are not protected even if they meet the activity recommendations. Thus, the results indicate that having high fitness is even more important for the health of the elderly than being as physically active as the authorities recommend.

Older adults who are fatigued walk on average 1000 fewer steps a day than other older adults. They also exercise less at moderate or higher intensity, and spend less calories during the day. The results may indicate that fatigue prevents elderly from being physically active, but physical inactivity likely also leads to more fatigue.

We also found that overweight participants, those with low fitness, and participants who had several other health problems were more exhausted and less physically active than others. In total, 9% of the participants reported fatigue.

Another paper shows that it's the activity level in the morning that is reduced among elderly with fatigue. By looking at hour-by-hour data from accelerometers, we found that the activity level for the rest of the day is not different between persons with and without fatigue.

The higher fitness, the higher is the level of physical activity in older adults. Moreover, the women in the Generation 100 study had a higher activity level than the men, and the activity level turned out to be higher in the summer than in the winter.

Maximum oxygen uptake, gender and season were the three most important factors that could tell us something about the physical activity level of the participants. This cross-sectional study is based on baseline accelerometer data from 850 Generation 100 participants.

In Generation 100 participants with worse lung function than a certain threshold, we found a clear association with fitness level: The worse the lung function, the worse the cardiorespiratory fitness. For participants who had better lung function than this threshold, however, maximum oxygen uptake was not limited by lung function.

In healthy people, it is the heart, not the lungs, that is usually considered the limiting factor for cardiorespiratory fitness. The lungs actually have a reserve capacity to transport oxygen to the blood even at maximum exercise. However, the threshold level we found for lung function to be important for fitness was well within what is considered normal lung function in persons aged between 70 and 77 years. The results may therefore indicate that age impairs lung function to such an extent that it affects the physical capacity of many healthy older adults.

When using accelerometers, one must reach a certain intensity level for it to be considered moderate or intense physical activity. The same absolute intensity threshold is used to make objective measurements of physical activity levels in women and men of all ages. However, many older adults have too low physical capacity to achieve these absolute intensity threshold, and will therefore end up in the category of physically inactive even if they exercise regularly at an intensity that is sufficiently high based on their own fitness level.

Therefore, we have established new threshold levels to describe moderate and intense physical activity with accelerometers in older women and men. Our threshold values are based on relative intensity, and take into account both that the average fitness of the elderly is lower than in younger people and that older women have lower fitness levels than older men.

Send us an e-mail:

cerg-post@mh.ntnu.no

Send us regular mail:

NTNU, Fakultet for medisin og helsevitenskap

Institutt for sirkulasjon og bildediagnostikk

Postboks 8905

7491 Trondheim

Visit us:

St. Olavs Hospital

Prinsesse Kristinas gt. 3

Akutten og Hjerte-lunge-senteret, 3. etg.

7006 Trondheim

Contacts, Generation 100

2025:

Solberg, A., Aspvik, N. P., Lydersen, S., Midttun, S., Reitlo, L. S., Steinshamn, S., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Helbostad, J. L., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2025). Effect of a 5-Year Exercise Intervention on Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Sedentary Time in Older Adults—The Generation 100 Study. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 1(aop), 1-9.

2023:

Reitlo, L. S., Mihailovic, J. M., Stensvold, D., Wisløff, U., Hyder, F., & Håberg, A. K. (2023). Hippocampal neurochemicals are associated with exercise group and intensity, psychological health, and general cognition in older adults. GeroScience, 1-19.

2022:

Carlsen, T., Stensvold, D., Wisløff, U., Ernstsen, L., & Halvorsen, T. (2022). The association of change in peak oxygen uptake with use of psychotropics in community-dwelling older adults-The Generation 100 study. BMC geriatrics, 22(1), 1-10.

Pani, J., Eikenes, L., Reitlo, L. S., Stensvold, D., Wisløff, U., & Håberg, A. K. (2022). Effects of a 5-Year Exercise Intervention on White Matter Microstructural Organization in Older Adults. A Generation 100 Substudy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience.

Pani, J., Marzi, C., Stensvold, D., Wisløff, U., Håberg, A. K., & Diciotti, S. (2022). Longitudinal study of the effect of a 5-year exercise intervention on structural brain complexity in older adults. A Generation 100 substudy. NeuroImage, 119226.

2021:

Zotcheva, E., Håberg, A. K., Wisløff, U., Salvesen, Ø., Selbæk,. G., Stensvold, D., & Erntsen, L. (2021). Effects of 5 Years Aerobic Exercise on Cognition in Older Adults: The Generation 100 Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sports Medicine, 1-11

Sokolowski, D. R., Hansen, I. T., RIsen, H. H., Reitlo, L. S., Wisløff, U., Stensvold, D., & Håberg, A. K. (2021). 5 Years of Exercise Intervention Did Not Benefit Cognition Compared to the Physical Activity Guidelines in Older Adults, but Higher Cardiorespiratory Fitness Did. A Generation 100 Substudy. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience

Letnes, J. M., Berglund, I., Johnson, K. E., Dalen, H., Nes, B. M., Lydersen, S., Viken, H., Hassel, E., Steinshamn, S., Vesterbekkmo, E. K., Støylen, A., Reitlo, L. S., Zisko, N., Bækkerud, F. H., Tari, A. R., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Sandbakk, S. B., Carlsen, T., Anderssen, S. A., Singh, M. A. F., Coombes, J. S., Helbostad, J. L., Rognmo, Ø., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2021) Effect of 5 years of exercise training on the cardiovascular risk profile of older adults: the Generation 100 randomized trial. European Heart Journal, ehab721

Berglund, I., Vesterbekkmo, E. K., Retterstøl, K., Anderssen, S. A., Singh, M. A. F., Helge, J. W., Lydersen, S., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2021). The Long-term Effect of Different Exercise Intensities on High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol in Older Men and Women Using the Per Protocol Approach: The Generation 100 Study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 5(5), 859-871.

Pani, J., Reitlo, L. S., Evensmoen, H. R., Lydersen, S., Wisløff, U., Stensvold, D., & Håberg, A. K. (2021). Effect of 5 Years of Exercise Intervention at Different Intensities on Brain Structure in Older Adults from the General Population: A Generation 100 Substudy. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 16, 1485-1501.

Lundgren, K. M., Aspvik, N. P., Langlo, K. A. R., Braaten, T., Wisløff, U., Stensvold, D., & Karlsen, T. (2021). Blood Volume, Hemoglobin Mass, and Peak Oxygen Uptake in Older Adults: The Generation 100 Study. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

2020:

Stensvold, D., Viken, H., Steinshamn, S. L., Dalen, H., Støylen, A., Loennechen, J. P., Reitlo, L. S., Zisko, N., Bækkerud, F. H., Tari, A., Sandbakk, S. B., Carlsen, T., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Lydersen, S., Mattsson, E., Anderssen, S. A., Singh, M. A. F., Coombes, J. S., Skogvoll, E., Vatten, L. J., Helbostad, J. L., Rognmo, Ø., & Wisløff, U. (2020) Effect of exercise training for five years on all cause mortality in older adults—the Generation 100 study: randomised controlled trial. The BMJ.

Rodrigues, J. A. L., Stenvold, D., Almeida, M. L., Sobrinho, A. C. S., Rodrigues, G. S., & Júnior, C. R. (2020). Cardiometabolic risk factors associated with educational level in older people: comparison between Norway and Brazil. Journal of Public Health.

Bye, A., Klevjer, M., Ryeng, E., Silva, G. J., Moreira, J. B. N., Stensvold, D., & Wisløff, U. (2020). Identification of novel genetic variants associated with cardiorespiratory fitness. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases.

2019:

Williams, C. J., Gurd, B. J., Bonafiglia, J. T., Voisin, S. A. C., Li, Z., Harvey, N., Croci, I., Taylor, J. L., Gajanand, T., Ramos, J. S., Fassett, R. G., Little, J. P., Francois, M. E., Hearon Jr., C. M., Sarma, S., Janssen, S. L. J. E., Caenenbroeck, E. M. V., Beckers, P., Cornelissen, V. A., Pattyn, N., Howden, E. K., Keating, S. E., Bye, A., Stensvold, D., Wisløff, U., Papadimitriou, I., Yan, X., Bishop, D. J., Eynon, N., & Coombes, J., (2019). A multi-centre comparison of V̇O2peak trainability between interval training and moderate intensity continuous training. Frontiers in Physiology, 10, 19.

2018:

Reitlo, L. S., Sandbakk, S. B., Viken, H., Aspvik, N. P., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Tan, X., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2018). Exercise patterns in older adults instructed to follow moderate-or high-intensity exercise protocol–the generation 100 study. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 208.

Viken, H., Reitlo, L. S., Zisko, N., Nauman, J., Aspvik, N. P., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Wisløff, D., & Stensvold, D. (2018). Predictors of Dropout in Exercise Trials in Older Adults. Medicine and science in sports and exercise.

Aspvik, N. P., Viken, H., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Zisko, N., Mehus, I., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2018). Do weather changes influence physical activity level among older adults?–The Generation 100 study. PloS one, 13(7), e0199463.

2017:

Stensvold, D., Sandbakk, S. B., Viken, H., Zisko, N., Reitlo, L. S., Nauman, J., Gaustad, S. E., Hassel, E., Moufack, M., Brønstad, E., Aspvik, N. P., Malmo, V., Steinshamn, S. L., Støylen, A., Anderssen, S. A., Helbostad, J. L., Rognmo, Ø, & Wisløff, U. (2017). Cardiorespiratory Reference Data in Older Adults: The Generation 100 Study. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 49(11), 2206.

Sandbakk, S. B., Nauman, J., Lavie, C. J., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2017). Combined Association of Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Body Fatness With Cardiometabolic Risk Factors in Older Norwegian Adults: The Generation 100 Study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 1(1), 67-77.

Zisko, N., Nauman, J., Sandbakk, S. B., Aspvik, N. P., Salvesen, Ø., Carlsen, T., Viken, H., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2017). Absolute and relative accelerometer thresholds for determining the association between physical activity and metabolic syndrome in the older adults: The Generation-100 study. BMC geriatrics, 17(1), 109.

Hassel, E., Stensvold, D., Halvorsen, T., Wisløff, U., Langhammer, A., & Steinshamn, S. (2017). Lung function parameters improve prediction of VO2peak in an elderly population: The Generation 100 study. PloS one, 12(3), e0174058.

Egerton, T., Paterson, K., & Helbostad, J. L. (2017). The association between gait characteristics and ambulatory physical activity in older people: a cross-sectional and longitudinal observational study using generation 100 data. Journal of aging and physical activity, 25(1), 10-19.

2016:

Aspvik, N. P., Viken, H., Zisko, N., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2016). Are Older Adults Physically Active Enough–A Matter of Assessment Method? The Generation 100 Study. PloS one, 11(11), e0167012.

Sandbakk, S. B., Nauman, J., Zisko, N., Sandbakk, Ø., Aspvik, N. P., Stensvold, D., & Wisløff, U. (2016, November). Sedentary Time, Cardiorespiratory Fitness, and Cardiovascular Risk Factor Clustering in Older Adults--the Generation 100 Study. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings (Vol. 91, No. 11, pp. 1525-1534). Elsevier.

Egerton, T., Helbostad, J. L., Stensvold, D., & Chastin, S. F. (2016). Fatigue alters the pattern of physical activity behavior in older adults: observational analysis of data from the generation 100 study. Journal of aging and physical activity, 24(4), 633-641.

Egerton, T., Chastin, S. F., Stensvold, D., & Helbostad, J. L. (2015). Fatigue may contribute to reduced physical activity among older people: An observational study. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences, 71(5), 670-676.

2015:

Hassel, E., Stensvold, D., Halvorsen, T., Wisløff, U., Langhammer, A., & Steinshamn, S. (2015). Association between pulmonary function and peak oxygen uptake in elderly: the Generation 100 study. Respiratory research, 16(1), 156.

Viken, H., Aspvik, N. P., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Zisko, N., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2016). Correlates of objectively measured physical activity among Norwegian older adults: the Generation 100 Study. Journal of aging and physical activity, 24(3), 369-375.

Zisko, N., Carlsen, T., Salvesen, Ø., Aspvik, N. P., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Wisløff, U., & Stensvold, D. (2015). New relative intensity ambulatory accelerometer thresholds for elderly men and women: the Generation 100 study. BMC geriatrics, 15(1), 97.

Stensvold, D., Viken, H., Rognmo, Ø., Skogvoll, E., Steinshamn, S., Vatten, L. J., Coombes, J. S., Anderssen, S. A., Magnussen, J., Ingebrigtsen, J. E., Singh, M. A. F., Langhammer, A., Støylen, A., Helbostad, J-, K., & Wisløff, U. (2015). A randomised controlled study of the long-term effects of exercise training on mortality in elderly people: study protocol for the Generation 100 study. BMJ open, 5(2), e007519.

2014:

Egerton, T., Thingstad, P., & Helbostad, J. L. (2014). Comparison of programs for determining temporal-spatial gait variables from instrumented walkway data: PKmas versus GAITRite. BMC research notes, 7(1), 542.